Forests And

Atmospheric Carbon Dioxide

Forest management directed at carbon sequestration could make a significant difference in global carbon sequestration over the near and medium terms. Traditionally, forest management has involved managing woodlands for the production of a single output—timber. Yet forests have always also been a means of sequestering carbon. In the past this ecosystem benefit went unnoticed and landowners were not compensated for this service. Forest managers would have ignored any carbon considerations in their management actions.

| . .  The long-term rewards you receive from your foresight will far outweigh your efforts. |

|

Suppose now, however, that annual payments were made for both the carbon sequestration and the timber extracted. Under this arrangement, timber and carbon sequestration could be viewed as joint products, and the timberland owner would have two market outputs to consider. |

As your forest matures, the timber stands become more valuable, as

does the value of its carbon sequestration services. Landowners must contract with an aggregated organization to have their lands included in a larger pool, so that they can accumulate enough carbon units to be eligible to trade on the open market. |  A young forest at work, sequestering carbon. |

. . .  |

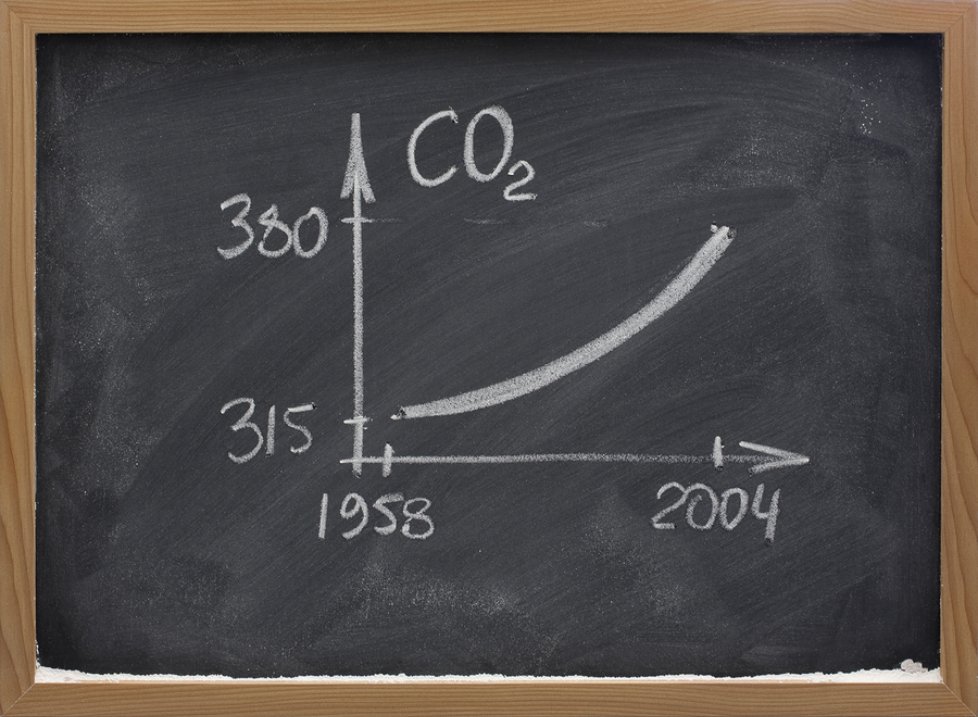

Forests operate both as vehicles for capturing additional carbon

and as carbon reservoirs. A young forest, when growing rapidly, can sequester

relatively large volumes of additional carbon roughly proportional to the

forest’s growth in biomass. An old-growth forest acts as a reservoir, holding

large volumes of carbon even if it is not experiencing net growth. Thus, a young forest will hold less carbon, but it is sequestering additional carbon over time.

|

. An old forest may not be capturing any additional new carbon, but can continue to hold large volumes of carbon as biomass over long periods of time. Managed forests offer the opportunity for influencing forest growth rates and providing for full stocking, both of which allow for more carbon sequestration. |  |

. .  |

To achieve this result, there must be a net increase in forests

so that the total forest biomass increases—or that it decreases less than would

be the case in the absence of such management. Sometimes, no overall net forest growth needs to occur. Ideally,

the net growth of the forest system is harvested sustainably by harvesting the

trees in the oldest age class, unless negative to positive growth. The age of the harvested class is defined as the harvest rotation age. Once mature, such a forest experiences no net increase (or decrease) in timber stock or harvest volumes over time. |

|  |

Finally, harvested wood that is converted into long-lived wood

products adds an additional stock of captive carbon.

Wood products do not last forever. Nonetheless, the global inventory of wood products increases when more products are added to the inventory than are removed from the destruction and dissipation of some products. |  |

or sequestered, in that stock.

to find out if your land will Qualify for CO2 credits click here.